Eugene Dupont and his Unique “Conic-Horn” Cornet.

This highly unusual cornet, in the collection of Bill Faust, is the only known example signed by E. Dupont during his years in England. Eugene Dupont was born “Jean Baptiste Victor Eugene Dupont” in about 1832, according to Margaret Downie Banks, in her history of C.G. Conn, “Elkhart’s Brass Roots. He is best known to us as partner with Charles Gerard Conn between 1876 and 1879. Assembling a biography of his life has been difficult, due mostly to the fact that he moved around a lot. Also, the name, Eugene Dupont, was not unusual, nor other combinations of his given names.

We know that he was French speaking, possibly born in Paris or in Belgium, and we have no primary sources telling us of his mechanical training before moving to England. The 1851 English census shows an 18 year old Eugene Dupont living with his family in Chester, England. The father of this family Louis Antoine is listed as a teacher of French. This may or may not be the same person. The partnership, Dupont, Mercadier et Cie. advertised in 1862, brass instruments with ‘pistons à perce plaine et sans angle’ (straight bore pistons, without angle). Again, there is no evidence that this was the same man. An omnitonic horn in the collection of the Musee de la Musique is marked “Fait par Dupont à Paris". This instrument was made in about 1818 and associated with maker Jean-Baptiste Dupont, who lived from 1785 to 1865. He may have been a relative, but more sources need to be found to tie all these threads together or determine otherwise.

We do know that he was in London working for Henry Distin by 1864. In that year Distin was awarded a patent for a new method of making pistons for valves that he promoted as “Patent Light Valves”. While Dupont’s name did not appear on that patent, when it was subsequently patented in France in 1865, he was listed as the inventor. The old method involved assembling the coquilles (tubes directing the bore through the pistons) into a tube with holes and silver soldering in place. This was then inserted into a slightly larger tube with holes drilled to line up with the inner piston’s holes and soft soldered in place. Dupont’s new idea involved simply silver soldering the coquilles into that outer tube, then machining it to size. The latter is the method that all makers of brass instruments today use for piston valves.

A decade later, while Dupont was living in Syracuse, New York, a newspaper article stated that he was “for many years superintendent of the renowned Besson's manufactory, in London, England”. There is no other evidence found for this statement, so we wonder if the journalist confused the two London factories. It is also intriguing to think that perhaps Dupont had worked for Besson in Paris, learning the trade before moving to London.

Eugene Dupont is found in primary sources, mostly for his political activities. By 1867, presumably while still working for Henry Distin, he became a French representative of the International Working Men’s Association. The best remembered members are Karl Marx, the representative of Germany and Holland and Frederick Engels, of Belgium and Spain. Dupont was elected President of the association in 1867. They were earnestly concerned with the conditions of the working class, and with the abuses of those in power. As today, there was journalistic support and sympathy for the movement as well as those that saw them as a corrupting influence. The International opposed the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and were accused of being closely associated with the Paris Commune, although the latter may not be true. The Commune was lead by socialist, anarchist revolutionaries after the violent coup by the Paris National Guard in late 1870. While at their founding, the International was mostly represented by Swiss and French members, after the war, it was mainly populated by English members and focused on the plight of working men in Great Britain.

Dupont was still deeply involved in the causes of the International in 1872, at which time he was living in Manchester. While there, he applied for patent protection for “improvements in musical wind instruments, and in the music holders attached to each”. A transcript of the application or actual patent granted has not yet been located, but it likely covered some of the design of the cornet being featured here. The pistons are made using his method patented in 1865. We are fortunate that the date was engraved on the bell, which is highly unusual on an instrument not being decorated for a special occasion. Perhaps he made this as a show piece to promote his talents, since he doesn’t seem to have been employed by Distin or Besson at the time. He likely carried it with him when he travelled to New York in October of 1874. This cornet recently surfaced at an estate sale in Elkhart, Indiana. So, he must have taken it with him to demonstrate his talents to Conn 15 months later.

The most visible design feature that is unique is the waterkey with a spring loaded pushrod. Arnold Myers pointed out that there is a Rudall Carte cornet with a similar waterkey, but which covers two holes. That likely dates just slightly later than this one. The newspaper mention of Dupont’s application indicates an improvement to the music holder. While the music lyre is missing, the round tapered mount socket is unique for instruments made in Britain. It is the same as made by American makers starting in the mid-1850s. The Bb mouthpipe shank appears to be original, although confusingly, it is stamped “42”, while the serial number stamped on the second valve casing is “41”. The size and font of the “4” are identical in both cases. The unique feature of the shank is that the mouthpiece receiver is a separate piece, soldered over the small end of the mouthpipe taper. While this is almost universal in piston valve cornets and trumpets today, it was highly unusual in the 1870s. The only other British made instruments exhibiting this design at that time was Bailey’s Acoustic Cornet made by John Kohler in London between 1862 and 1873. Dupont was likely familiar with these cornets.

The most remarkable feature of this cornet is that every tube (aside from outer slide tubing) is tapered inside. In the second photo below, you can see that each inside tube has a sleeve soldered over it to fit into the outside slide tubes. Each of the inside tubes has a slight taper, both inside and out. Each slide crook also has a very slight taper. The name “Conic-Horn” obviously refers to the entire bore being conical, however slightly. With no indication on the cornet that it was covered by any patents, it is possible that Dupont was not successful in obtaining his patent that he applied for the previous year. The concept that the ideal brass instrument should have as much of its bore tapered as possible was not a new one, but this was the idea taken to it extreme. It was revisited, or re-invented 40 years later by Ernst Albert Couturier in Indiana. His patent of 1913 simplified the idea by forgoing tuning slides for each valve. Couturier expanded the concept to all sizes and types of brass instruments, including the slide trombone.

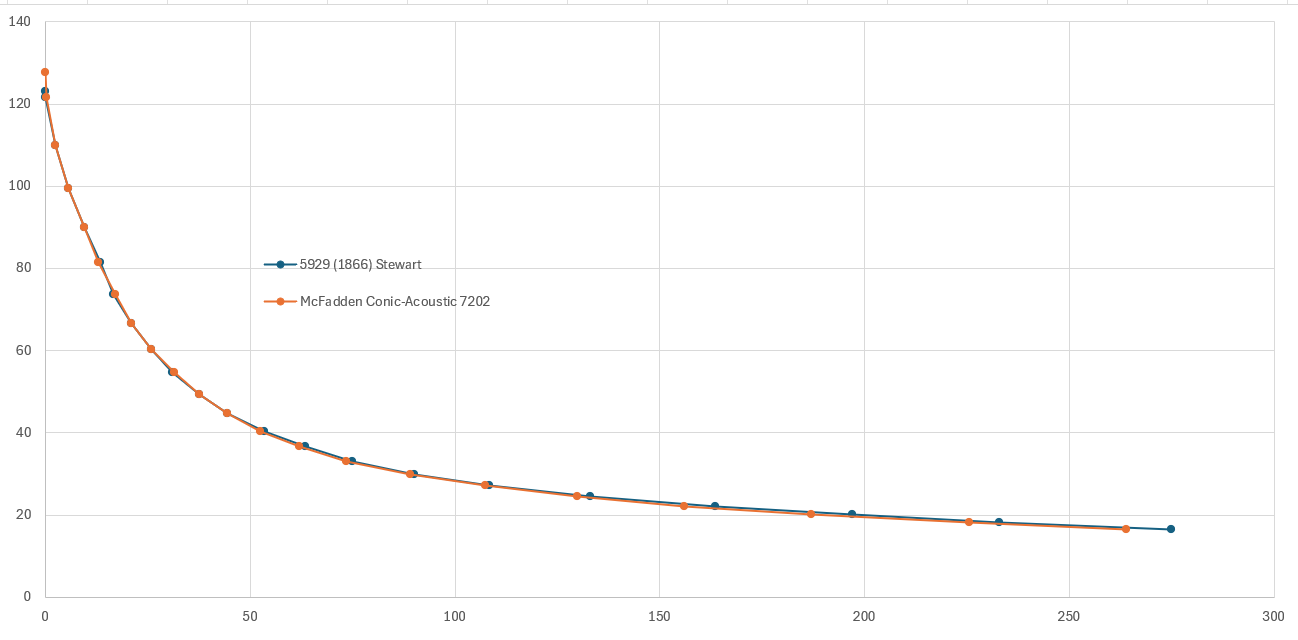

As already mentioned above, Eugene Dupont travelled to New York in October of 1874. He and fellow passenger Louis Duchaussoy were both listed as musicians, although nothing further has been found regarding the latter. By July of 1875, Dupont was working for George McFadden, in Syracuse, New York. As a youth, McFadden was an apprentice to a brass instrument maker in Liverpool and then lived in London until he left for the US in 1865. It is possible that the two knew each other in London, perhaps as co-workers, but this can only be speculation for now. The cornet that they produced together in Syracuse was called the “Conic Acoustic Cornet”. While it’s design is quite different from the Conic-Horn, there are obvious links. The pistons are made by the same single wall construction as the Distin patent. While the valve tubing is all cylindrical, it does have a larger proportion of conical tubing than other cornets. The mouthpipe is very long and the taper continues all the way through the tuning slide assembly. Those slide tubes are tapered inside, machined on the outside to fit the outer slide tubing. It has the tapered round lyre mount socket, but has a conventional water key.

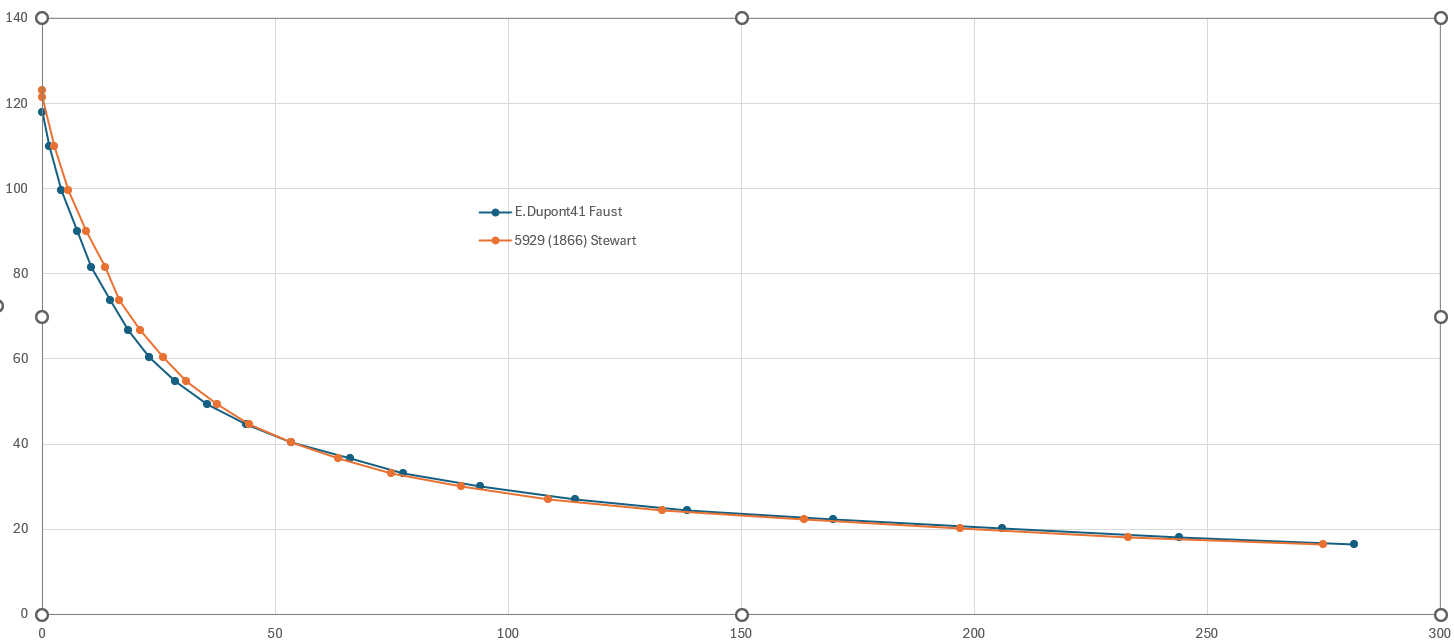

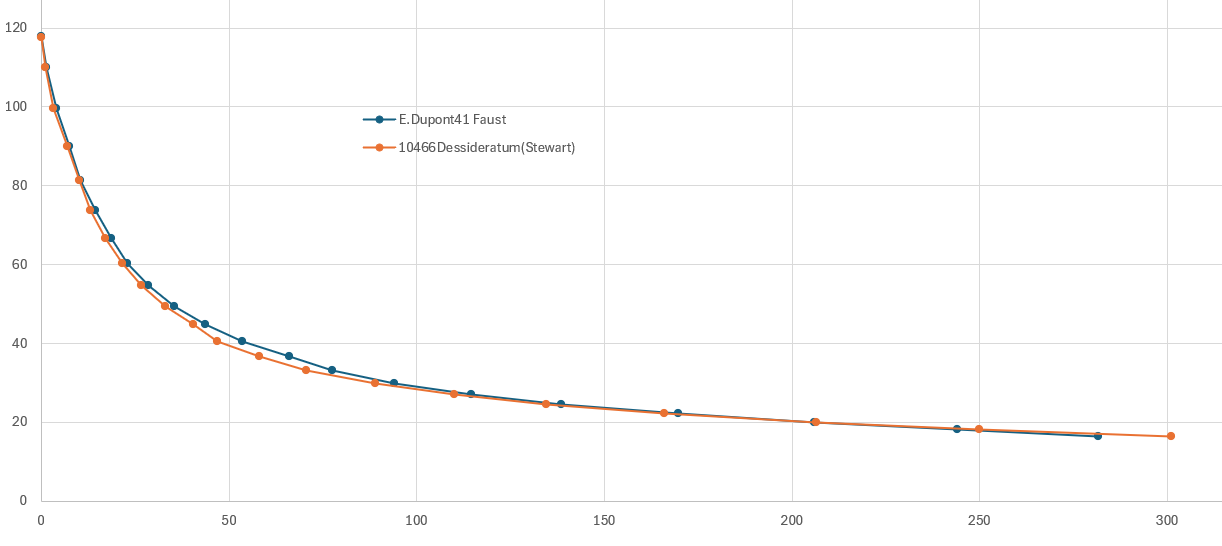

During these years, most cornet bells were copies of, or at least inspired by those of Antoine Courtois or F. Besson. As you can see in the charts below, the Dupont bell is similar to both Courtois and Besson, but varies by a similar degree at different sections. The McFadden bell is so close to Courtois’ bell that it indicates a lot of effort in the copy.

Dupont must not have been very satisfied with his work with McFadden. According to Dr. Banks, he was in Elkhart, Indiana, in January of 1876, meeting with C.G. Conn, making plans for a partnership. They lost no time in designing and producing a new cornet in time to be displayed at the Centennial Exhibition, which opened May 10th. Their new design, called the “Four-in-One Cornet” was pitched in Eb with crooks for tuning to C, Bb and A and a valve assembly design that allowed for this wide range of tuning. They jointly applied for a patent in January, 1877, which was granted January 22, 1878. The partnership was dissolved in March, 1879, nine months before their second patent was granted that December. That was for a piston valve design with only two ports, that they called "Equa-Tone valve" or "Conic Clear Bore Valve" in different catalogs.

A remarkable similarity of engraving style on the cornets of Dupont, McFadden and the early Conn and Dupont instruments can’t be ignored. Up to that time, it was quite rare for any but the most elaborate presentation instrument to be so well decorated. Perhaps Eugene Dupont saw importance in decorating his instruments. Not all McFadden and Conn and Dupont instruments are engraved like this, but the similarities are rather interesting. C.G. Conn continued to have most of his instruments elaborately engraved and set a standard that was soon followed by most other US makers. Even importers of inexpensive brass instruments offered extensive engraving for a few extra dollars.

He continued his activities supporting the working class. In 1878, he was the Elkhart representative of the Central Committee of the International Labor Union. Headquartered in New York, it was also known as the “American Commune”, an ironic name in this story.

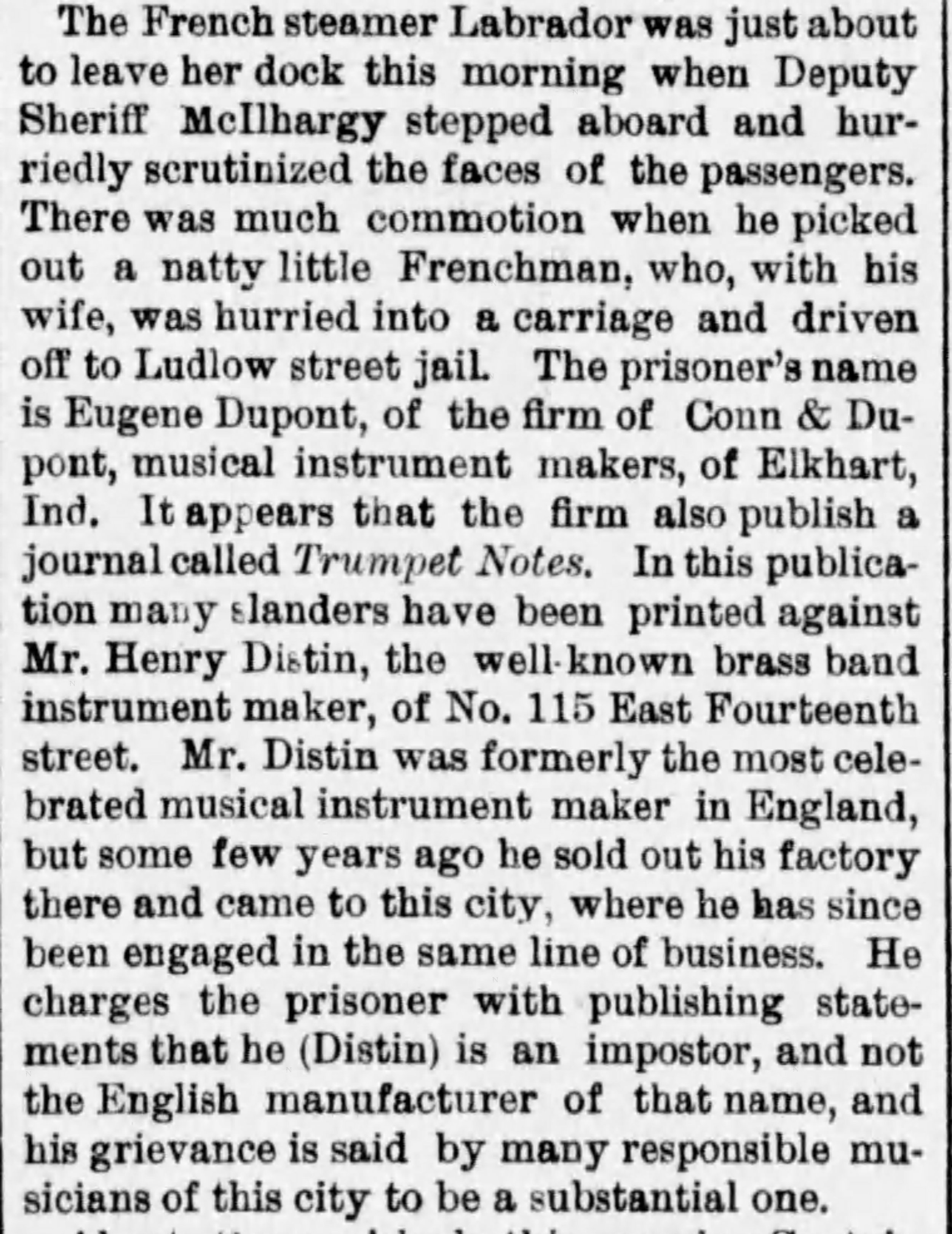

On September 10, 1879, Dupont and his wife were in New York City, where they boarded the steamship Labrador, presumably to sail to France. A deputy sheriff came aboard and arrested them and took them to jail, where he was charged with libel against Henry Distin. Dupont had published in “Trumpet Notes” that Distin’s success in London was due solely to his (Dupont’s) skill and knowledge of brass instrument making. There must be court records to be found with results of this charge, but Eugene was able to travel to France very soon after, without his wife. He returned to New York in November, aboard the Canada, arriving from La Havre. He had with him three younger men all described as “Factor” (“facteur” being the French word for maker). One of the three was Ferdinand Coeuille, who was listed in Elkhart in 1880 as Instrument Maker, presumably working for Conn. He was later in Philadelphia, working for J.W. Pepper and/or Distin and then with his own shop in Camden, NJ in 1890, custom building cornets and making mouthpieces. The other two names have not been associated with brass instrument making, but it seems likely that they were also brought to Elkhart to work for Conn.

Dupont moved to Chicago in September of 1880. No records of his naturalization are known, but in Chicago, he became delegate for Cook County General Campaign Committee for the Republican Party, supporting James Garfield and Chester Arthur.

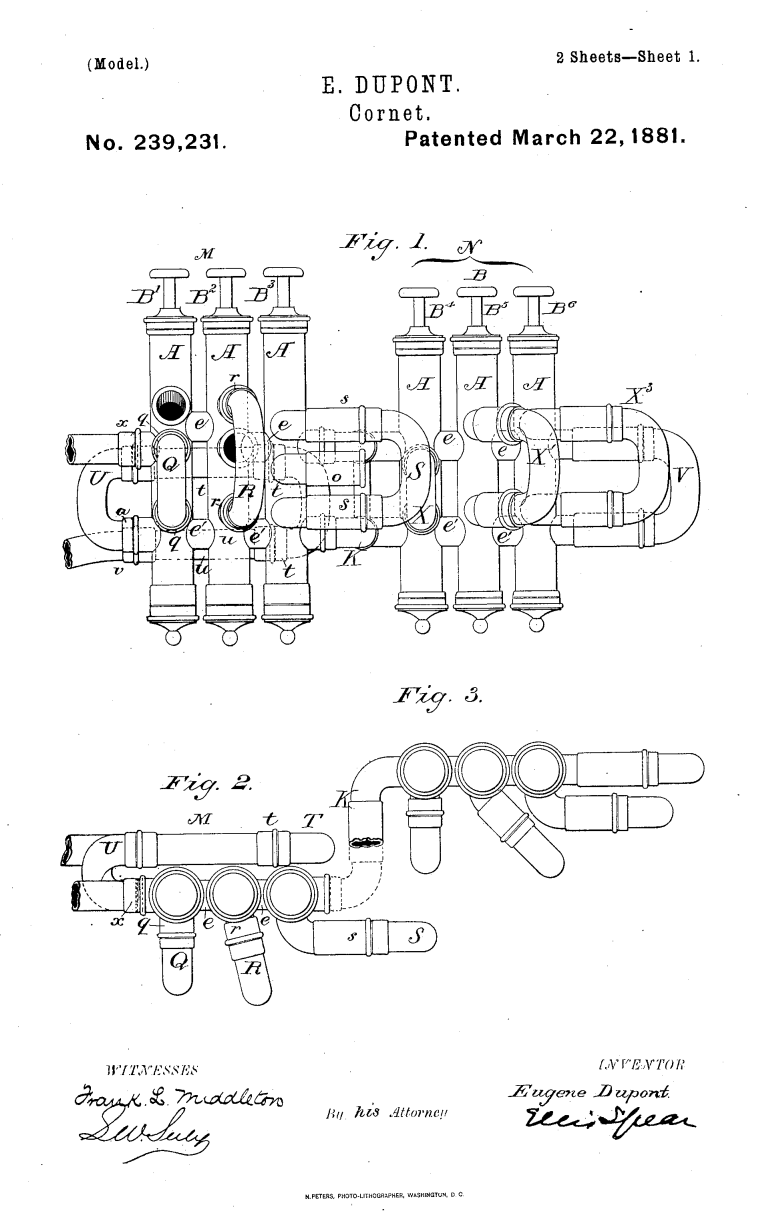

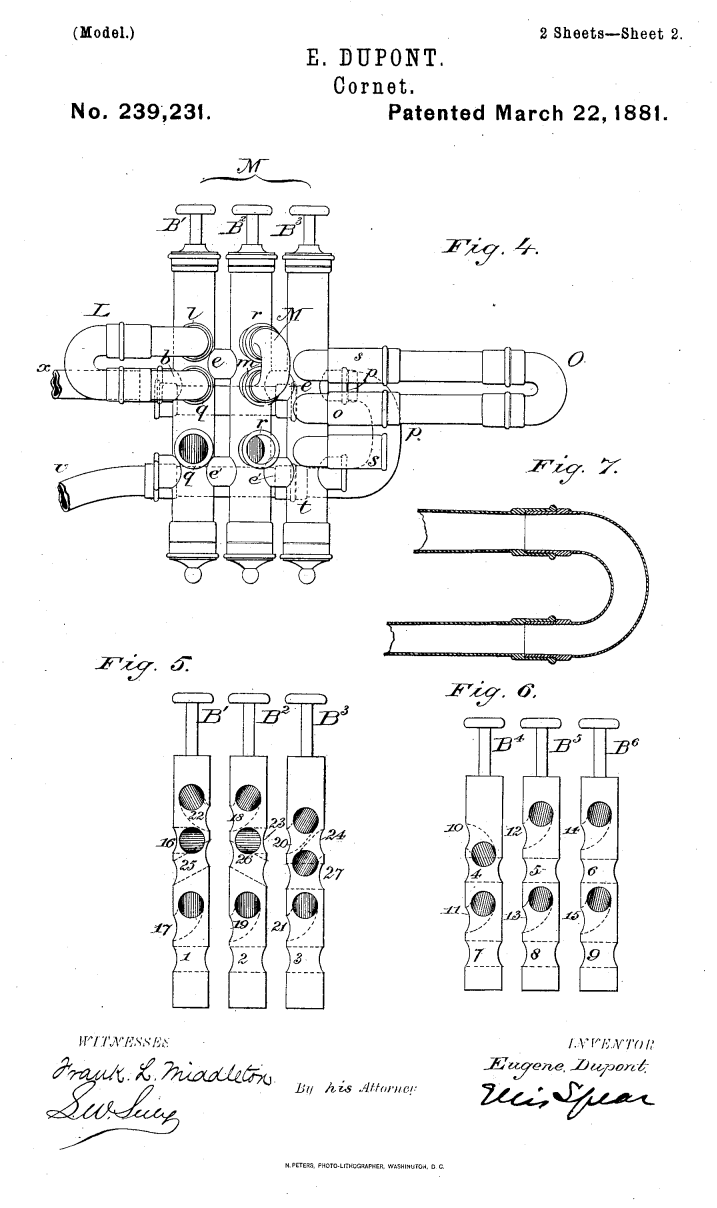

He applied for another patent for brass instrument design, which was granted on March 22, 1881. This was for instruments with six independent valves, like those made by Adolphe Sax, although more commonly seen in Belgian trombones. In Dupont’s design, an assembly of three of the valves could be detached from the other three, and by reconfiguring the slides in the remaining valve assembly, the instrument could be played with conventional valve combinations. It is hard to imagine a market for his new device and he died just four months later. Judging by the accuracy of the patent drawings, shown below, a prototype of this valve section was likely constructed, but isn’t known to have survived to our time. At the time of his death of phthisis pulmonalis (pulmonary tuberculosis), July 26, 1881, he had been living in Washington DC for less than three months. He was listed as a widower and was 49 years old. Nothing has been found about Dupont’s wife aside from that she was arrested with him in New York.

Jean Baptiste Victor Eugene Dupont was able to endow successful new designs for other makers to profit from, but wouldn’t or couldn’t stay involved. His method for constructing “patent light valves” was a success in his time and is the method used by all piston valve makers today. His other ideas were not nearly as important, but intelligent and well reasoned. He was instrumental in the start of production of a Midwestern US company that became the world’s largest less than thirty years later. And yet, he was passionately involved in the International Working Men’s Association for at least seven years. He must have been a man of great intellect and passion, but unfortunately, we have only this sketchy biography, pieced together as best we can, in an attempt to understand.