essay 2 - THE HISTORY OF THE ORCHESTRAL f TRUMPET of THE ninteeNTH CENTURY

CHAPTER 1. THE MIDDLE NINETEENTH CENTURY (1840-1870)

The valved trumpet and the cornet-a-piston finally established a presence in most orchestras of Europe during the middle decades of the nineteenth century and the three-valve design stimulated this development. The French brass maker François Périnet, perfected what was to become the modern piston valve in Paris in 1839. His design was improved by Courtois and G. Besson during the 1850s and employed on French and English cornets and trumpets, replacing the Stölzel valves.[1] Wieprecht’s “Berlin” styled piston valves also remained popular both in Prussia and Paris with military band instrument makers including Adolph Sax. Riedl’s rotary valves were increasing in popularity in Germany and Berlioz mentions their widespread use by 1843.[2] The Périnet valve is essentially the modern piston valve and needs no further discussion. The Berlin valve was never very popular on orchestral instruments and is, therefore, outside the scope of this dissertation. The rotary valve, however, is quite important to the history of orchestral trumpets and is relatively unfamiliar to trumpeters outside of Germany.

The Rotary Valve

The rotary valve most commonly associated with German trumpets during the middle of the nineteenth century was similar to that employed today on horns and tubas. This rotor piston rotated on a brass bearing which was covered by a metal cap as they are today. The rotors were driven by an articulated lever system with a clock-spring return mechanism. The metal springs were enclosed in cases and the most expensive models featured a ratchet wheel spring tension adjusting mechanism called a “Remontier” device. (See Figure 1) Modern German trumpets are still built in the articulated lever configuration but lack the Remontier spring tension mechanism. Modern rotary valves seen most commonly on French horns employ a string connecting the finger lever to the rotor. The use of this type of string-action rotary valve is similar to those found on all instruments by American brass instrument makers of the middle nineteenth century. Most European manufacturers adopted this design much later, during the early twentieth century, and in modified form.

One further design detail characteristic of European rotary valve trumpets during the nineteenth century was the use of pin-type rotor stops. This design featured a thin metal rod or pin, approximately one-quarter inch in length, attached to the top of the valve casing. Cork dampening flanges fastened to the rotor axle made contact with the pin. This pin acted as a stopper, limiting the back and forth motion of the rotor, ensuring the proper alignment of the air channels. (See Figure 1) Nineteenth century German and Italian rotary valve trumpets examined by the author all feature this type of pin stopper. The modern design locates the valve casing and the pin in the rotor axle. This design became standard at the turn of the twentieth century and is still in use today.

Figure 1. Close-up of rotary valve mechanism on a German C trumpet. Note the pin-type rotor stops and the Remontier valve tensioning devices. - Streitwieser Collection

Valved Trumpets in Austria and Germany

The valved trumpet seems to have established a regular presence in German orchestras earlier than in other countries in Europe. Hector Berlioz’s frequent travels to Germany provide direct evidence of the role of valved trumpets in orchestras at this time. In a letter from Berlin to Mademoiselle Bertin, dated November, 1843, Berlioz stated that rotary-valved trumpets were in general use throughout Germany and that the German trumpets were far superior to those made in France.[3] An earlier reference to the use of valved trumpets in opera and symphony orchestras in Germany is found in the 1837 article by C. G. Reissiger previously referred to. Reissiger was a staunch supporter of the use of the natural trumpet and horn and asked conductors to begin a dialogue concerning the “rapidly increasing” use of valved brass instruments in their ensembles. Reissiger rejected these new instruments because of their inferior tone quality. He conceded that valved instruments must be used for certain operas by French and Italian composers and criticized composers for using valved instruments at all. The article also makes reference to the increasing popularity of high-pitched “trumpets” like those built by Wieprecht for the military bands of Berlin. The author predicted facetiously that one day these small “octavetrumpets” and “trumpetinas” will replace the softer high woodwinds in the louder music.[4] High pitched B-flat trumpets were not just used in Wieprecht’s military bands in Berlin. Joe Utley and Sabine Klaus have documented dozens of specimens in museums in Europe and the United States that date from the middle of the nineteenth century. They demonstrate that these instruments were common in bands in Germany, Austria, and particularly, Bavaria.[5]

Reissiger’s comments indicate that there was still resistance to the valved trumpets in some orchestras in Germany, particularly before 1840, and many trumpet parts from that era that exhibit notes not included in the harmonic series seem to have been intended for stopped trumpets. Felix Mendelssohn utilized some non-harmonic series tones in his Reformation Symphony, op. 107, in D major after writing trumpet parts employing only the natural harmonic series in his earliest orchestral works. The first movement, scored for two trumpets in D, exhibits three tones which could only be played on the natural trumpet using stopped technique. (See Figure 2) These notes, e'-flat, d'-flat, and f', were easily achieved by the partial insertion of the hand in the bell, lowering each harmonic a half step to the prescribed pitch. Other non-harmonic tones, including a' and b' natural, are found in the other movements. Karl Bagans (b. 1791), a Royal Prussian chamber musician[6] included a chart of stopped notes available on the natural trumpet in his article in Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, which clearly indicates the availability of the above notes during the 1830s.[7] It must be noted that the slide trumpet could play these notes as well; however, I have found no evidence that slide trumpets were employed in orchestras in Germany during the nineteenth century.

Figure 2. Excerpts from the first trumpet part of Mendelssohn’s Symphony #5 op. 107 showing notes intended for stopped trumpet.

Symphonies One and Two by Robert Schumann also appear to have been written for stopped trumpet. (See Figure 3) Schumann’s Symphony No. 1, op. 38, in B-flat major written in 1841 was scored for two trumpets crooked in low B-flat. As was the case with the Reformation Symphony, these parts were intended to be played on natural trumpets. The only exceptions to the natural notes are written e'-flats in the first and third movements and written a’s in the last movement. These are notes that can only be played using stopped technique on the natural trumpet. Schumann’s C major Symphony, op. 61, written between 1845 and 1846, was also written for natural trumpet employing stopped technique.

It might be argued that Schumann and other composers during the early nineteenth century wrote trumpet parts for natural and stopped trumpets, unaware that the newer valved instruments may have actually been employed in the orchestras to play their music. A statement by F. L. Schubert in 1866 that stopped trumpets were almost never used in German orchestras[8] combined with the statement by Berlioz in 1843 (previously mentioned) and Eichborn in 1881,[9] that valved trumpets were in general use in Germany during the early 1840s, might lead one to this conclusion. However, Schumann corresponded with Mendelssohn regarding the writing of the First Symphony and one letter dated October 22, 1845, reveals clearly that stopped technique was used in the performance of the First Symphony. “Do you remember the first rehearsal of the ‘Spring’ Symphony in the year 1841… and the ‘stopped’ trumpets and horns at the beginning? It sounded as if the orchestra had a cold in its head; I can’t help laughing when I think of it.”[10]

Figure 3. Excerpts from Schumann’s Symphonies

But Schumann seems to have begun scoring for the valved trumpet by the late 1840s and clearly employed it in both his Third and Fourth Symphonies. (See Figure 3) Schumann’s earliest valved trumpet scoring shows the use of valves most consistently in the second trumpet part. The first trumpet in the Third Symphony was written almost entirely in notes of the harmonic series and was probably intended to be played on either a natural trumpet, or valved trumpet without the use of valves, simulating a natural trumpet. The second trumpet part was written in consistent octaves with the first. As was often the case in classical and early romantic trumpet music, composers tried to score the first and second trumpets in octaves whenever possible. Of course, with the natural trumpet, the harmonic series often prevented the possibility of writing octaves in the lower second parts. But the employment of the chromatic valved trumpet allowed composers, for the first time, to achieve a consistent octave interval, and Schumann treated the trumpets in octaves on almost every note in the Third Symphony. Schumann called for trumpets crooked in E-flat in the Third Symphony and never scored the first trumpet above written e''. The second trumpet however, opened a whole new range in the low register as it played octaves with the first. The second trumpet part was consistently written down to low D and even reaches low C on occasion. Adam Carse has stated that valves on early trumpets were often employed only as instant crook change devices[11] but Schumann’s use of the valved trumpet is much more progressive, exploiting the true chromatic capabilities of the instrument. When Schumann did call for a crook change from F to E in the first movement of the Fourth Symphony (revised c. 1851), he probably did so for a specific purpose, to avoid the awkward fingerings and intonation problems associated with the keys of F-sharp and B major. Schumann even included a short rest in the music, allowing the performers to affect the crook change.

Franz Liszt’s earliest orchestral music (mostly scored by August Conradi and Joachim Raff) clearly call for the valved trumpet. The tone poem Les Preludes (1848 – Conradi?) was scored for two valved trumpets crooked in low C. The trumpets were frequently treated in unison to reinforce the important melodic lines given them. The range of the two parts extends from low C to high g'' Liszt added a third trumpet part in the Faust symphony and increased the demands on the section by requiring solos of both the first and second players. It is arguable that the dramatic and descriptive nature of Liszt’s symphonic poems (and Wagner’s operas) would not have been possible without the important chromatic trumpet parts that play such as important role.

Richard Wagner’s early trumpet scoring is similar to Liszt’s but shows a decidedly French influence. Wagner lived in Paris between 1838 and 1842 where Berlioz, Meyerbeer, and Halévy regularly employed valved cornets or trumpets in their operas. Probably under their influence, Wagner scored his first opera, Rienzi (1840), for a combination of natural and valved trumpets. Wagner chose to employ valved trumpets for some of the music and natural trumpets for the rest as Berlioz had done previously, but ignored the cornet. The instrumentation for Rienzi included two valved and two natural trumpets in the orchestra and six valved and six natural trumpets on stage. The first and second trumpets in the pit orchestra were marked “ventil” in D, and the third and fourth “ordin” in D. Wagner discontinued scoring regularly for the natural trumpets after Rienzi, and the first trumpet parts for his later operas were all written for valved trumpets.

One aspect of Wagner’s treatment of the trumpet in his later operas and music dramas was unusual and has raised questions among trumpet players. Wagner insisted on writing his valved trumpet parts with frequent crook changes. This in itself was not unusual, but the frequency of his crook changes was unprecedented. Most nineteenth century composers insisted on notating the valved trumpet parts in the key of C whenever possible. They employed the age-old practice of crooking to change the pitch of the F trumpet to E, E-flat, D, and even C to facilitate this practice.[12] This practice is explained by Rode who stated that early valved trumpet players always attempted to use the open notes of the natural harmonic series whenever possible to imitate the sound of the natural trumpet.[13] As music became more chromatic, the trumpeters were forced to use their valves on a regular basis. This increased reliance on valves made crook changing unnecessary and by mid-century, many trumpeters were abandoning the practice, preferring to transpose instead.

Wagner chose to ignore this trend and actually increased the frequency of crook changes in his later trumpet parts. Lohengrin, and all his later operas, feature frequent and sometimes almost instantaneous crook changes. The trumpets in ACT III of Lohengrin are required to begin the Prelude crooked in C and, one bar later, to change crooks to E. Later, they play in D and, with no break at all, change to C. The chromatic nature of his trumpet music indicates that Wagner intended the use of valved trumpets yet he must have been aware that trumpeters could not possibly change crooks as quickly as he sometimes requires. This begs the question, why?

It is possible that Wagner used crook changes for timbral contrast. Performances of his operas often employed a double trumpet section. The players might have alternated on the crook changes, one playing while the other changed crooks in preparation for the next change. Bassett mentioned the distinctly noticeable effect of crook changes on trumpet tone color[14]and early trumpet tutors by Dauvernè and Kosleck often required crook changes, presumably for the tonal contrast. However, this assumption seems unlikely because some of Wagner’s crook changes occur right in the middle of phrases where a timbral contrast would have been disruptive.

Another explanation has been offered by Vincent Cichowicz, my trumpet professor at Northwestern University and a twenty-five year member of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He took Adam Carse’s view that Wagner sometimes employed the valves of the F trumpet purely as instant crook change devices.[15] The crook changes included in the music direct the performer to use certain valve combinations to place the trumpet in the prescribed keys, whereupon the part is played employing as many notes from the harmonic series as possible. A final explanation has as its basis, Wagner’s great respect for Berlioz. Wagner seems to have required crook changes at points of modulation in the music as Berlioz earlier instructed in his treatise on orchestration.[16] It must be pointed out however, that Berlioz was addressing his remarks to the use of natural trumpets rather than valved trumpets, and was stating the obvious. Wagner however, seems to have ignored this fact and in deference to Berlioz, required the appropriate crook changes as if his trumpets were in fact, valveless.

Wagner’s peculiar scoring practices required trumpeters to master the technique of transposition. Transposing natural trumpet parts presented no great difficulties. Wagner’s chromatic harmonies however, resulted in the addition of many accidentals to trumpet parts and performers had to work very hard to master this new challenge. One of the most famous trumpeters in Germany during the middle of the nineteenth century, Ernst Sachse, immortalized himself by writing a set of transposition Etudes for E-flat trumpet in 1850.[17] These studies are still used today.

While composers still wrote mostly for the F trumpet with crooks at this time, there is evidence that performers in some German orchestras were actually beginning to use high B-flat and C military band trumpets instead. Wieprecht built some of the first high B-flat trumpets for the Prussian military in 1829 and they became quite popular in bands during the middle part of the century. Dauvernè and many trumpeters like him began their careers as bandsmen[18] and it is certainly possible that these players brought their high-pitched band instruments with them into the orchestras. One of the earliest cases of a high B-flat trumpet in orchestral use is credited to Adolf Scholz of Breslau. He is reported to have employed a high B-flat trumpet in the orchestra exclusively by 1850.[19] Julius Kosleck, the famous Prussian trumpeter, is also reported to have petitioned the Royal Ministry of Culture in Berlin to allow the high B-flat trumpet into the opera orchestra as early as 1855. He praised the instrument’s “beautiful” and “radiant tone” and, after an investigation, the request was evidently granted.[20]

However, at least two nineteenth-century writers indicated that the standard orchestral trumpet of the mid-nineteenth century was still pitched in low F. (See Figure 4) It was the opinion of F. L. Schubert that the high trumpets were becoming popular if one could transpose, but that it was impossible “… to find them in the orchestra music.”[21] F. A. Gevaert wrote that the high B-flat and A trumpets were used primarily in military bands and that modern players (c. 1880) used them to play only the high orchestral parts like the Parsifal solo.[22] It is difficult to state with certainly, but it appears that by 1870 many first chair trumpeters in Germany employed the high-pitched trumpets while most of the second and third players retained the F trumpet.[23] The high-pitched trumpets were employed by first-chair players for two reasons: the shortened length of the instrument made playing technically demanding passages much easier, and also facilitated greater accuracy in the upper register. The French employed the cornet in their orchestras for the same reasons.

Orchestral Trumpets and Cornets in France and England

Valved trumpets were rarely, if ever, used in the French orchestras during the middle of the nineteenth century. This may have been the resulted of a mid-century debate in Paris led by Carse and Dauvernè over the proper role of the valved trumpet in the orchestra relative to the natural trumpet. Carse wrote: “The question became not so much whether valved instruments were a desirable addition to the orchestra, but whether they were desirable as substitutes for the natural instruments.”[24] Dauvernè discussed this problem in his Methode at some length. He concluded that the natural and slide trumpets were clearly superior to the valved instruments in every way except rapid facility. Dauvernè concluded that the valved trumpet was not a desirable substitute for the natural trumpet and his influence was very great in Paris at the time.[25] In fact, the French taste for the natural and slide trumpets, coupled with the extensive use of the cornet-a-piston, ensured that the valved trumpet would not completely establish its dominance until the first performance of Lohengrin in Paris in 1891.[26]

Figure 4. Two nineteenth century Austrian F trumpets. Top: Karl Frey, Bottom: Anton Wild - Streitwieser Collection

The cornet-a-piston (hereafter called simply the cornet) became popular in Paris almost immediately after its invention by Hallary and Labbaye. Dauvernè confirmed that cornets were already popular as “dilettante” instruments as early as the 1830s[27] and the instrument achieved its modern configuration in the 1840s with the addition of Périnet valves. The French cornet’s lead pipe was quite long and usually bent three times before entering the third valve. This contrasted with the German rotary-valved trumpet design, which featured a short lead pipe entering the first valve. (See Figure 4) The most important difference, however, between the cornet and the trumpet, other than the obvious length of tubing, was the conical bore and mouthpiece shape. The cornet’s tubing was largely conical with the exception of that in the valve area, and mouthpiece was originally shaped like the horn mouthpiece with a deep funnel-shaped cup. It was not until the 1850s that the shallower, bowl-shaped cup, characteristic of the trumpet mouthpiece, was adapted to the cornet.[28] (See figure 5)

Figure 5. Nineteenth century cornet and trumpet mouthpieces - Streitwieser Collection

One of the earliest of the great cornetists of the nineteenth century began his career as a trumpet student of Dauvernè at the Paris Conservatory. Joseph Jean-Baptiste Arban (1825-1889) taught trumpet at the Academy of Military Music and later taught the first class in the cornet and saxhorn at the Conservatory. In 1864 he wrote his famous Grande Method… for cornet and saxhorn and in it, revealed many interesting details concerning the use of cornets in France during the middle of the nineteenth century. Arban wrote in the “Introduction” to Grande Method…: “It may appear somewhat strange to undertake the defense of the cornet at a time when this instrument has given proofs of its excellence; both in the orchestra and in solo performance.”[29] Arban went on to describe the cornet as the equal to the flute, clarinet, and even the violin in both the eyes of the composer and the public[30] and he felt that the valved cornet should be taught at the Conservatory. To that end, he wrote many letters to David Auber, the director of the Paris Conservatory. On November 2, 1868, Arban wrote: “It is a fact that hardly anybody plays the trumpet anymore and that the provincial theaters—and even those in Paris—no longer have artists playing the instrument. Almost everywhere the trumpet has been replaced by the cornet-a-piston… It is generally known that one can be an excellent trumpeter and yet starve to death, whilst everybody can live comfortably by playing the cornet-a-piston.”[31] Arban’s letters seem to have been persuasive for in 1869 he was appointed to the position of professor of cornet at the Conservatory. The trumpet class however, continued to meet separately and the valveless trumpet continued to be studied exclusively.[32]

It is ironic that the composer who was responsible for the use of cornets in French orchestras was most displeased by that practice. Hector Berlioz considered the sound of the cornet to be “vulgar”[33] and believed the valved trumpets employed in Germany to be much superior.[34] However, Berlioz was not able to convince influential French trumpet and cornet players like Dauvernè and Arban that the valved trumpet was a superior instrument. He was therefore forced to score for the cornet to achieve the chromatic effects he wanted from the trumpet section. Berlioz considered the natural trumpet to be the superior instrument and the cornets, because of their poor tone quality, were employed to fill in the “holes” in the harmonic series. Berlioz limited the upper range of the natural trumpets because he was convinced that high c''' was only playable by English and German players.[35]

The most important problem created for modern performers by the use of cornets in orchestral music from the mid-nineteenth century is whether to use cornets when playing the parts today. The answer seems clear in the case of Berlioz. Berlioz thought the tone quality of the cornet inferior to that of the trumpet and used it primarily to fill in the non-harmonic series notes for the trumpet section. It would therefore, seem sensible today to play the cornet parts in Berlioz’s music on trumpets. The early twentieth century (1927) French trumpeter Merri Franquin agreed: “modern trumpets should be given the parts written for the cornets in the early operas.”[36] Julius Kosleck, (1825 - 1905) first trumpeter in the 2nd infantry guard regiment band in Berlin and professor of trumpet and trombone at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik,[37] presented a different opinion in the introduction to his Grosse Schule für Cornet à piston und Trompete (c. 1872). And interestingly the German Kosleck, was an early supporter of the use of cornets in the orchestra: “We now-a-days associate the ‘trumpet’ with the old principle, the martial, sonorous manner of playing and ‘cornet’ with the former ‘clarin,’ the soft cantabile style. It remains the composer’s task to keep this dual character…well in view and not write passages for the cornet which would be more effective if written for the trumpet or the reverse…The abuse of having in German orchestras two trumpets only, or in the majority of French and English ones, two cornets only, has its source in the insufficient general knowledge about these instruments….Let performers, therefore, exert themselves, as well as composers, to apply in the right way the capabilities and fine qualities of this instrument and to insist on its dual character everywhere. And this all the more so because Meyerbeer has shown us the way. Let us, therefore, preserve the twofold character by having both the cornet and the trumpet in the orchestra.”[38] Kosleck’s opinion seems not to have been shared by many of his countrymen as the use of cornets in German orchestras never became common.

English orchestras continued to employ the slide trumpet during the middle decades of the nineteenth century but the cornet made inroads here as well. According to Geiringer, the cornet was quite popular in England as a substitute for the trumpet. He supported this practice by using an argument that was probably common during the nineteenth century: “Berlioz and many other recent writers after him complained that the cornet was a trivial instrument, and that its tone was shrill and vulgar, yet it may well be that they were unconsciously attributing to the instrument itself the quality of the light music in which it was most frequently employed.”[39] The light music referred to would include salon music and band music.

It is Edward Tarr’s belief that the popularity of the cornet during the mid-nineteenth century had two positive influences on the future of the trumpet: an increase in solo literature, and the development of the high B-flat trumpet. With the notable exception of Anton Weidinger’s commissions for Haydn and Hummel, few major composers were thought to have composed serious solo music for the chromatic instrument. However, Tarr has recently identified a number of previously unknown solo works for the “Romantic trumpet,” as he calls it, which should improve the repertoire for the instrument when they become more generally known.[40] And after the rise in popularity of the cornet as a solo instrument around 1850, the trumpet was indeed, treated in a more virtuosic and soloistic manner by many orchestral composers, particularly Liszt and Wagner. Tarr also observed that the cornet stimulated the increased use of high-pitched B-flat and C trumpets in the orchestra, eventually replacing the F trumpets.[41] Though clearly a valid conclusion, it is a matter of opinion whether this trend was a positive influence on the development of the trumpet or a negative one.

In summary, it is clear that the split in the evolution of the trumpet continued to deepen during the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Despite the attacks on the cornet by such important musicians as Berlioz and Dauvernè, this offshoot of the trumpet family tree continued to grow in popularity, often at the expense of the trumpet. The valved F trumpet still dominated orchestras in Germany and Austria but in France and England (and the United States), its use was superseded by the slide trumpet, the natural trumpet and especially the cornet.

The valved trumpet found in most German orchestras after 1840 made a significant impression on the music of most Romantic Era composers. The dramatic extremes in dynamics and brilliant brass sounds of Liszt’s tone poems and Wagner’s operas would not have been possible had they been writing for natural or slide trumpets or even the cornet. The middle of the nineteenth century was the period in which the trumpet and cornet were in use simultaneously as two separate instruments. But by the end of this period, these two separate developments began to merge back together, creating the instrument that is today called the B-flat trumpet.

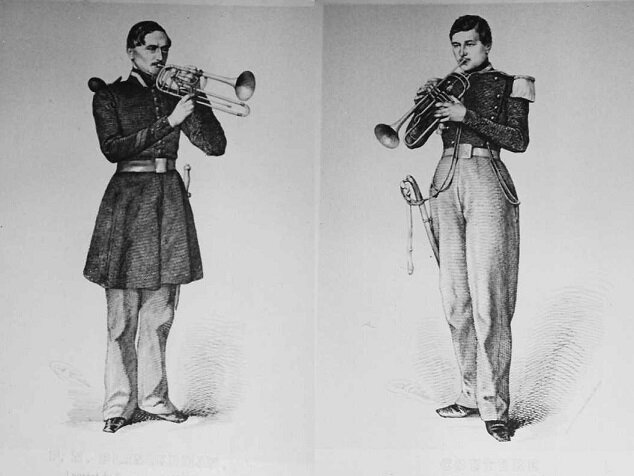

Figure 6. Two French trumpeters - Slide trumpet, P. N. Blanckeman 1849 Paris Conservatory. Valved trumpet, M. Couture Military School, student of Dauvernè. (Bad Sackingen Trumpet Museum)

[1] Philip Bate, The Trumpet and Trombone, (New York: W. W. Norton, 1966), p. 168.

[2] David Cairns, The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz, (London: Victor Gollancz, 1969), p. 318.

[3] Ibid., p. 321.

[4] C. G. Reissiger, “Über Ventilhorner and Klappentrompeten,” Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, Vol. XXXVII, 1837, pp. 608-609.

[5] Joe R. Utley and Sabine K. Klaus, “The “Catholic” Fingering—First Valve Semitone: Reversed Valve Order in Brass Instruments and Related Valve Constructions,” Historic Brass Society Journal, Volume 15, 2003, p. 85.

[6] Edward H. Tarr, “The Romantic Trumpet,” Part One, The Historic Brass Society Journal, Volume 5, 1993, p. 222.

[7] Karl Bagans, “Freie Aufsätze,” Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, No. 43. Berlin: 1829, p. 338.

[8] F. L. Schubert, Die Blechinstrumenten der Musik, (Leipzig: 1866), p. 50.

[9] Herman Eichborn, Die Trompete in Alter und Neuen Zeit, (Leipzig: Breitkopf and Härtel, 1881), p. 53.

[10] Robert Schumann, The Letters of Robert Schumann, translated and edited by Karl Storck, (London: John Murray, 1907), p. 249.

[11] Adam Carse, The History of Orchestration, (London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, & Co., 1925), p. 270.

[12] Hector Berlioz, Grand Traite d’Instrumentation et l’Orchestration, (Paris, 1843), p. 212.

[13] Theodore Rode, “Wiederholter Wunsch zur Grundung…,” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Vol. LXXVIII, (1882), p. 267.

[14] Henry Bassett, “On Improvements in the Trumpet,” Proceedings of Musical Association, Vol. III, (1876-77), p. 1441.

[15] Carse, op. cit., p. 270.

[16] Berlioz, op. cit.

[17] Edward H. Tarr, Die Trompete (Bern: Halweg Verlag, 1977), p. 122.

[18] F. G. A. Dauvernè, Methode pour La Trompette, (Paris: Chez G. Brandus, Dufour et Cie, 1857), p. XXII.

[19] Tarr, Die Trompete, op. cit., p. 124.

[20] Heinz Burum, “Erlebnisse und Erfahrungen mit Kollegen und Schulern – 50 Jahre als Trompeter und Trompetenlehrer,” Das Orchester, Vol. XXXII, No. 4, (1984), p. 320.

[21] F. L. Schubert, “Uber den Gebrauch u. Missbrauch der Ventilinstruments in Verbindung m. anderen Instrumente,” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Vol. LXI, Pt. 1 (1865), p. 98.

[22] F. A. Gevaert, Neue Instrumentenlehre, (Leipzig: Otto Junne, 1887), p. 287.

[23] Tarr, op. cit. p. 124.

[24] Carse, op. cit., p. 270.

[25] Dauvernè, op. cit., p. 152.

[26] Merri Franquin, “La Trompette et la Cornet,” Lavignac, Encyclopedie de la Musique, Part III, Vol. II (Paris: Delagrave, 1927), p. 1609.

[27] Dauverné, op. cit., p. 230.

[28] Anthony Baines, Brass Instruments, (London: Farber & Farber, 1974), p 230.

[29] Jean-Baptiste Arban, Arban’s Method for the Cornet and Saxhorn, (Boston: White, 1881), p. 4.

[30] Ibid, p. 15.

[31] Jean-Pierre Mathez, “Arban (1825-1889),” Brass Bulletin, No. 10, (1975), p. 14.

[32] Tarr, op. cit., p. 123.

[33] Berlioz, op. cit., p. 224.

[34] David Cairns, The Memories of Hector Berlioz, (London: Victor Gollancz, 1969), p. 321.

[35] Berlioz, op. cit., p. 212.

[36] Franquin, op. cit., p. 1609.

[37] Edward H. Tarr, ”Kosleck, Julius.” Grove Music Online, retrieved 13 Mar. 2021, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000015405.

[38] Julius Kosleck, Grosse Schule für Cornet à piston und Trompete (c. 1872), in Julius Kosleck’s School for the Trumpet, revised and adapted by Walter Morrow, (London: Breitkopf and Hartel, 1907), p. IV.

[39] Karl Geiringer, Musical Instruments, 2nd edition, (London: George Allen & Unwin LTD, 1945), p. 287.

[40] Tarr, “The Romantic Trumpet,” Part One, op. cit., p. 232.

[41] Tarr, Die Trompete, op. cit., p. 124.