Eb Soprano by George Freemantle Restoration

This very interesting and rare instrument was offered in a New Hampshire country auction, purchased by a dealer and immediately offered to John and Rebecca Bieniarz, to become part of a growing collection of mid-19th century American brass instruments. It is quite well preserved overall, with the only major damage to the bell curve, miserable solder job on the valve section and a few missing parts. Most often the tuning mouthpipe shank is missing from this sort of instrument, but in this case, it was jammed in so tight, there was no possibility that it was going to be lost.

The restoration was mostly straightforward, one of the greatest challenges was removing the first and second valve cap rings that had been securely soldered in place by the previous repair. The close up in the fourth photo below shows the area that had been covered by solder. The valves are in excellent condition and it seems to play as well as the best Graves and other Boston made sopranos. I'm not presenting this instrument for any particular challenge in the restoration, but rather to tell the following story.

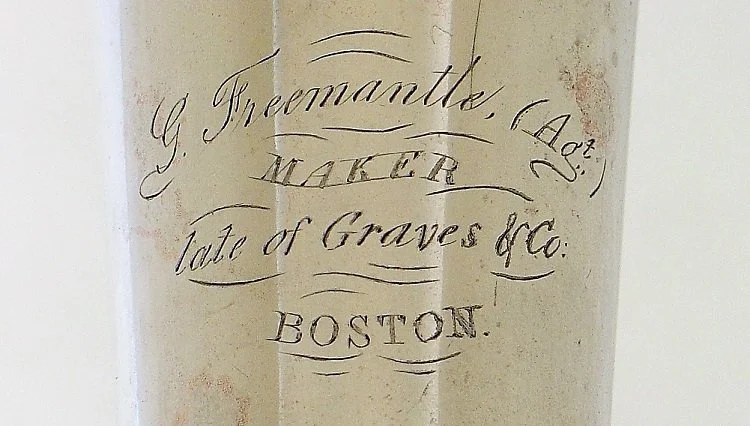

There are only about eight brass instruments known that are marked similarly to this Eb valve bugle and they are all close copies of those by Graves & Company. From the Boston City directories we have learned that George Freemantle went to work in the shop that was shared by E.G. Wright and Graves & Co. (68 Albany St.) in 1858 when he was about 54 years old. When Wright moved out of that shop in 1860, Freemantle stayed with Graves until they moved out by 1864. During 1864, Freemantle was occupying that address by himself and was presumably when these instruments were made.

Of the known instruments, this seems to be the only one that has "(Ag't.)" following his name. I can only speculate that this is for "agent", causing confusion as to whether he was claiming to be the maker or the sales agent. In the 1860 census, at the same home address, George Sr. is listed as a musician and his son, George Jr. as a musical instrument dealer. This might lead us to believe that it was George Jr. that was working for Graves, but it is believed that it was the father that was the instrument maker. It is certainly possible that they were both working in that shop at the time.

I've only worked on one other Freemantle instrument, a tuba for Mark Elrod and in both cases, I find evidence that Freemantle wasn't an accomplished maker. Certain parts are of the same very high quality and design as used on Graves instruments, obviously purchased from other makers, perhaps Graves themselves. Other parts show a lack of skill. In the tuba, it was mostly in the forming and bending of the tapered tubes, but not in the fabrication of the bell or valve section. In this soprano, it is only obvious in the bend of the bell. Not only is it an uneven curve, but there is an obvious kink near where it joins with the third valve. This is never seen in the better makers and I know from experience that this is not a difficult part to bend neatly. This flaw is easily seen in the sixth photo. Just as in the tuba, the lack of skill in forming some parts doesn't seem to hinder the acoustics of the skilled design.

As mentioned above, the two George Freemantles can easily be confused and I had come to believe that it was the younger that had been the brass instrument maker and that the father had died in the 1860s. I have now corresponded with direct descendants that assure me that the father was the instrument maker and it was the son that had died in 1864 at the age of 29 years. Both of them were born in England, emigrating when George Jr. was about three years old. The father played flute, harp, organ and presumably piano, but I haven't been able to determine which instruments, if any, that the son played.

A single action harp, awarded a silver medal in the exhibition of the 1881 Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association was entered by Freemantle and a harp described as from about 1865 is in the collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. By 1881, George Sr. would have been 76 years old. Before his son's death, George Sr. seems to have been a financially stable musician and music teacher paying taxes on real estate valued between $4000 and $9500, while after that date, he got involved in a number of businesses and was insolvent at least twice.

George Jr. served as "mechanic" with the 47th Massachusetts Regiment September 1862 until September 1863. This unit was made up of Boston merchants and they had a band attached, but I haven't been able to determine if he also played in the band. Even though his unit did not see the brutal action that many other solders did during those years, it is tempting to speculate that his death (by suicide) was in part caused by what he experienced. I'm sure that there is more to be learned about the two Georges Freemantle.